I worked as a Java developer on a trading system for close to 2 years.

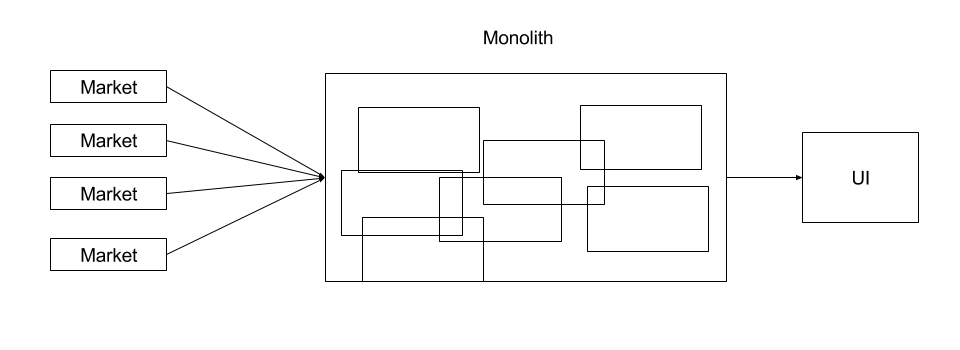

It was a fairly large project. The application connected to 5 different markets each with different API (XML, FIX, proprietary etc). To massage the trade, application had to access close 7 systems, outside our purview, to access reference data. The code base itself was around few hundred thousand lines of code.

We faced lot of issues due to the monolithic nature of our architecture

Code maintenance

It was easy to step on each other’s shoes when multiple developers access the same codebase. Creating branches can be helpful in such cases, but using Subversion (instead of Git) can make the merging complicated especially at scale.

Build and deploy

- Testing fixes in an environment, say UAT, required building entire codebase. For us, this meant 30 minutes of coffee break.

- This did not scale well. 12 developers multi-tasking bug-fixes and features additions, lead to huge number of concurrent builds (along with serious coffee addiction).

- Deploying a complete fix, might accidentally deploy other developer’s partial fix. All the code needed to be checked-in atomically (which was difficult to enforce).

- It became terribly important to know state of codebase, and schedule of building it; which meant lot of communication overhead within the team.

Latency

- To reduce the latency of accessing external systems we wanted to cache reference data.

- Was not possible with 32-bit Java (tell me about it!) i.e. 1.8GB heap space.

- Alternative was to use external caching solutions, but our manager insisted on creating an in-house distributed cache, which we did (I’m sorry Redis, my hands were tied).

These issues called for drastic change in architecture and processes. We had never heard the term microservices before, but that’s what we ended up with. If you are new to the term microservices, please read Martin Fowler’s excellent introduction.

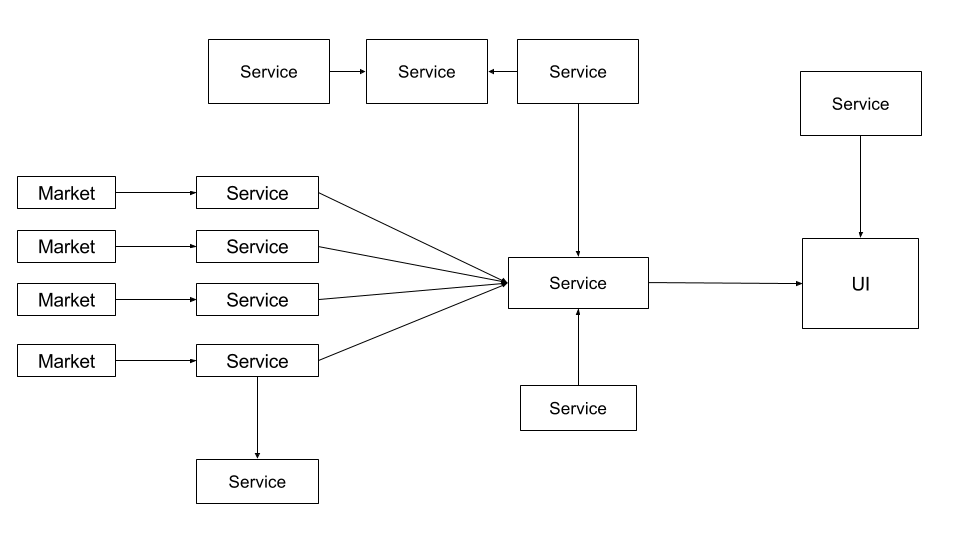

From monolith to microservices

Step 1: Identify independent pieces of the application

- Break down application into components, each responsible for single unit of functionality. For us, it translated to ‘sub-system connecting to a single external system’

- Create separate subversion (VCS) tree for each component

Rejoice! No more codebase conflicts amongst developers. As a bonus, we started owning components instead of code packages.

Step 2: Expose the service

- Expose functionality of that component as an API

- Expose cache if service deals with data (we used our in-house custom cache)

- Document the APIs in team wiki

Now for any new code, developer can just refer to the API of dependent services, without worrying about the internals. Though deciding on the API itself should be a thorough process. Otherwise, dependent services may need to keep updating the code, to keep up with API changes.

Step 3: Make service discoverable

- Avoid hardcoding configuration (host-port) values of dependent services

- Instead, identify services with logical names

- Expose this using service discovery tool like Zookeeper (We used an in-house company-wide solution)

Zookeeper might be an overkill for an application with limited scalability requirements and limited number of services. Alternative would be to create a well-known service, that provides configuration of other services.

Step 4: Data exchange format

We made a mistake of using Kryo as our serializer instead of JSON/XML. Having to maintain same version of JARs across the services proved difficult and we had to revamp our entire build system detailed in another post.

Alternative was to split the JAR (holding data classes) itself into multiple subsets, but it was not feasible at the time.

Choosing serialization format can be tricky.

XML or JSON

- Pros: Readable. Makes debugging easy. Backwards compatible.

- Cons: Network overhead. Slow. Maintenance of serializer and deserializer every time a data class updates.

Kryo (binary format)

- Pros: Concise. Fast.

- Cons: Needs same version of POJO on both ends. Not backwards compatible. Debugging and replay of messages is difficult.

Step 5: Address failure of services

- If a dependent services exposing cache is down, use stale cache (if use-case allows)

- Preferably display it on the UI, so that trader/user is aware if certain data-set is stale or unavailable

- Setup alerts for the dev/support team to rectify the issue

Step 6: Update build and deploy process

- Update build system to allow each service to be built and deployed independently

- Since we used Kryo, if a POJO representing data was updated, we had to built all services using that POJO

Miscellaneous:

- Microservices call for each service having its own database. We had a common database, though every service owned a subset of data (this addresses issues like eventual consistency).

- Our most important piece of data was a trade object, which was owned by a single component for each market. This way we were able to skip distributed transactions entirely.

- So a service would update the trade

- Send it across to owning component (which was anyways required to communicate with the market)

- Owning component would validate, persist the update, and distribute updated trade back to services/UI

In the end, the resultant architecture aka microservices, was lot more flexible, modular and maintainable. The processes became more streamlined and we started moving more swiftly as a team.

Tags: